Over the past two decades, long-running debates about the purposes and practices of humanistic inquiry have been refocused as a debate about the uncertain fate of the humanities in a digital age. Now, with the advent of digital and computational humanities, scholars are discussing with a new urgency what the humanities are for and what it means to practice them. And many suggest that the surfeit of digital data is unprecedented and are calling for new methods, practices, and epistemologies.

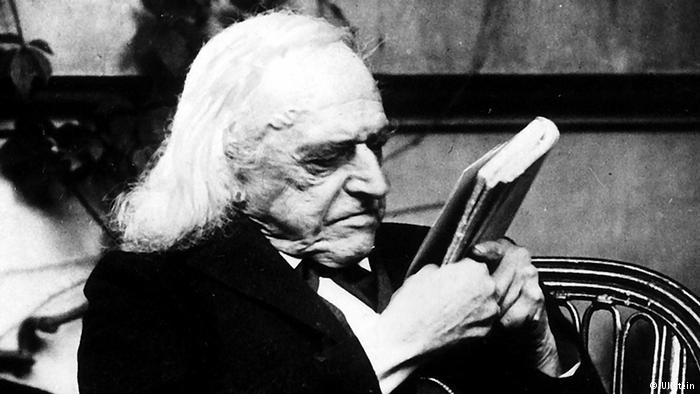

This article considers these claims in light of a longer history of what Lorraine Daston has called “practices of compendia”––practices of collecting, collating, and interpreting massive amounts of data. It focuses, in particular, on the late nineteenth-century German historian Theodor Mommsen and the range of projects he initiated and led as secretary of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Mommsen invented the “big humanities” and what his contemporaries termed the “industrial” model of scholarship, a model that helped create a new, modern scholarly persona and a distinctly modern ethics of knowledge.

[This is an abstract for: Wellmon, C. (2017) “LOYAL WORKERS AND DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS: BIG HUMANITIES AND THE ETHICS OF KNOWLEDGE,” Modern Intellectual History, 1-40. doi: 10.1017/S1479244317000129. PDF]